Uncategorized

Uncategorized

In light of the multiple thousands of denominations existing over and against Je...

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

By: ECO Team

One of the great dangers of systematic theology is our ability to pay little attention to the history behind doctrine. For example, why do we make a big deal out of the virgin birth of Jesus? The answer to that has been different at different times. In the Apostles’ Creed, which developed from a very early tradition in the Roman church, the motive in confessing the virgin birth was most likely a response to the challenge of Docetism, the belief that Jesus wasn’t really human, he just seemed to be. The virgin birth affirmed that Jesus is the son of God, and the son of Man from birth, not by adoption or just in appearance. Later, the virgin birth was used to defend certain ideas of how original sin is transmitted. From the late 19th century through today, it is often a test–case for how “liberal” or “conservative” a Christian is.

Though the words of the Apostles’ Creed have not changed, those who confess it have often had different understandings of what it means throughout Christian history. We are using the same biblical truth to combat different false beliefs in different times. But those who have written confessions have sometimes used Scripture to validate their own cultural values.

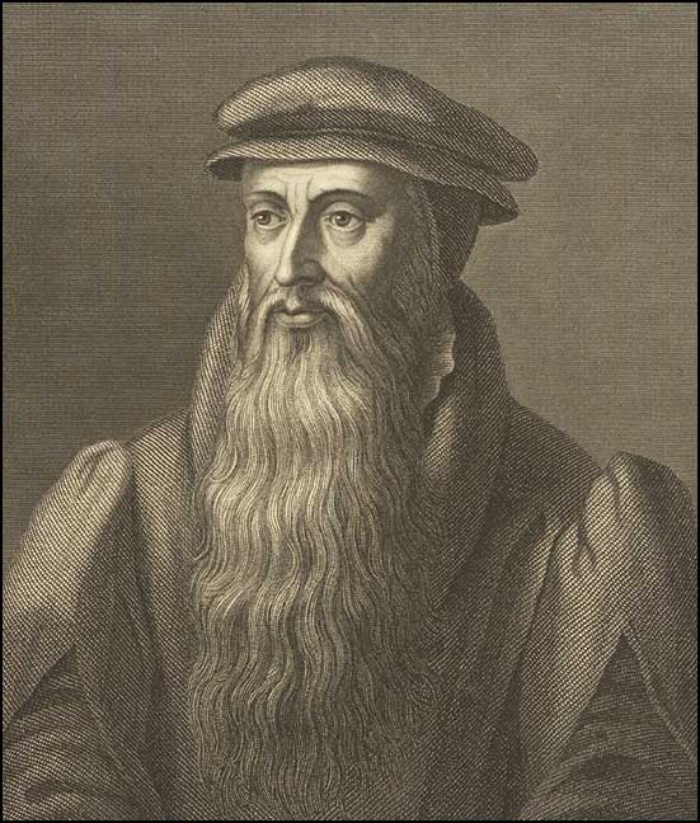

Take the Scots Confession (1560), for example. Written in part by John Knox, one of the founding fathers of Presbyterianism, it addresses some specific issues of his day. One of these is women in ministry. Knox had already written an infamous piece (anonymously), The First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women (1558), designed to lambast the reign of two Catholic queens, both named Mary, and of women in leadership generally. This backfired when the Protestant Elizabeth I came to the throne of England. She never forgave him for it. But included in the Scots Confession chapter XXII is a prohibition against women performing the sacraments.

This sixteenth century view was widespread, perhaps universal. But it’s far too easy and simplistic to just blame patriarchalism, after all, there were a lot of queens! Rather, one of the reasons the church seems to have prohibited women from positions of sacramental authority, apart from the stock arguments we’ve all heard, had to do with the fight against heresy. In the early church, women had a very high place for Roman standards. Indeed, Christianity strongly appealed to women, a fact pagan detractors seized upon. But the church began to limit the roles of women by the second century. Justo Gonzalez in The Story of Christianity, speculates that this may have happened, in part, as a response to Gnosticism which taught that all material reality was evil. Christianity taught that God was good, the creation was good, and that the distinction of male and female was important because flesh is important. It is, perhaps, in affirming the flesh that a complementarian position arose. We know that by the time of the Council of Nicaea (325), women were disallowed from much of church leadership.

How then do we reconcile the authority of confessions with our core values and beliefs in ECO, specifically “Egalitarian Ministry” in this example case?

We don’t. The reality is, confessions are the beliefs of a people in a place and time. As part of the people of God, we are part of a living history, and we don’t need to amend that history to make it fit our times and our preferences. This is why we have a list of Essential Tenets that we hold from the tradition we have received. But this does not mean we cannot confess anew what it is we believe, though to do so would always be temporary. One of the major shifts that Christianity brought to the world of ideas (with a lot of influence from Judaism) was the importance our story, here and now. We are not part of an endless cycle, nor are we “just passing through”. We believe in a God who purposes history, and writes his own version of it. He is writing his own book of life and we’re characters within it. Our temporary lives have eternal consequences, and so do our contextualized beliefs and confessions. Some of what we believe will be embarrassing to future generations. Some of it will be highly instructive, maybe even heroic. Part of living within the story is having the maturity to discern the wisdom of our forebears and to use it to critically assess our own lives and beliefs. We also learn that history is never a simple line from repression to liberation, and we do not necessarily live at its high or low or end point. We are in God’s story of reconciling the world to himself and we must proceed with wisdom, for we are God’s workmanship (Eph 2:10).

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

In light of the multiple thousands of denominations existing over and against Je...

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

My first pastoral call was to the First Presbyterian Church of Winnfield, a litt...

Uncategorized

Uncategorized

This semester, I’m teaching “The Holy Spirit and the Church.” Our primary textbo...